Ilkley and the Anti-Suffragist League: a very short history

Archaeologist and historian Rebecca Batley explores ... 🗳️

Well over a hundred years ago, Ilkley and Yorkshire towns like it were at the centre of the suffragette movement. While the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), one of the main organisations fighting for women to have the right to vote, was set up in the living room of Emeline Pankhurst's house in Manchester, notable members of the movement – such as the indomitable sisters, Catherine and Helen Tolson, and Adela Pankhurst, daughter of Emeline – could regularly be found walking, campaigning and recruiting on the streets of the town. In 1908, for instance, a WSPU demonstration was held at Ilkley Tarn, with Emmeline herself in attendance, attracting scores of people who came to hear her and other women speak and argue their case.

For many today, the suffragettes are heroes, iconic women who fought back and won in the face of almost overwhelming male oppression – and Ilkley is rightly proud of its suffragettes whose names now commonly feature in the plethora of literature on the subject. Few, however, are aware that Ilkley was also home to a branch of another organisation: The Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League (WNASL).

The WNASL was founded in July 1908 as a collective protest against suffragism. Their progress was chronicled in the Anti Suffrage Review and the first edition, which was published in December 1908, proudly declared that its executive committee was headed by Margaret Child Villiers, the Countess of Jersey, a notable critic of the suffragist movement.

Another prominent member was Mary Augusta Ward (also known as Mrs Humphry Ward), who considered the suffragettes to be nothing more than “terrorists”. She expounded the argument at the heart of the WNASL that it would only be through “the special knowledge of men” that the problems facing Britain could be solved. This argument was a popular one and its adoption spearheaded the organisation's northern expansion into towns like Ilkley, where the magazine was widely bought.

In her opinion, a man’s right to vote was, for example, his reward for fighting for king and country and representing the empire. It was a flawed argument, as all working men who made up the majority of soldiers did not themselves gain the vote until 1918 (prior to then, two out of every five men were unable to vote). Nevertheless, this was a popular argument that the WNASL expressed regularly.

The following year, the Anti Suffrage Review also acknowledged that a “civil war” was now being fought among women for their future, with one side determined to win women the right to vote – and have a say in the politics of the country – and the other equally as determined that no such law be passed. A microcosm of this civil war could be found in many towns like Ilkley. Suffragism and anti-suffragism spread quickly as women mobilised all over the country on both sides.

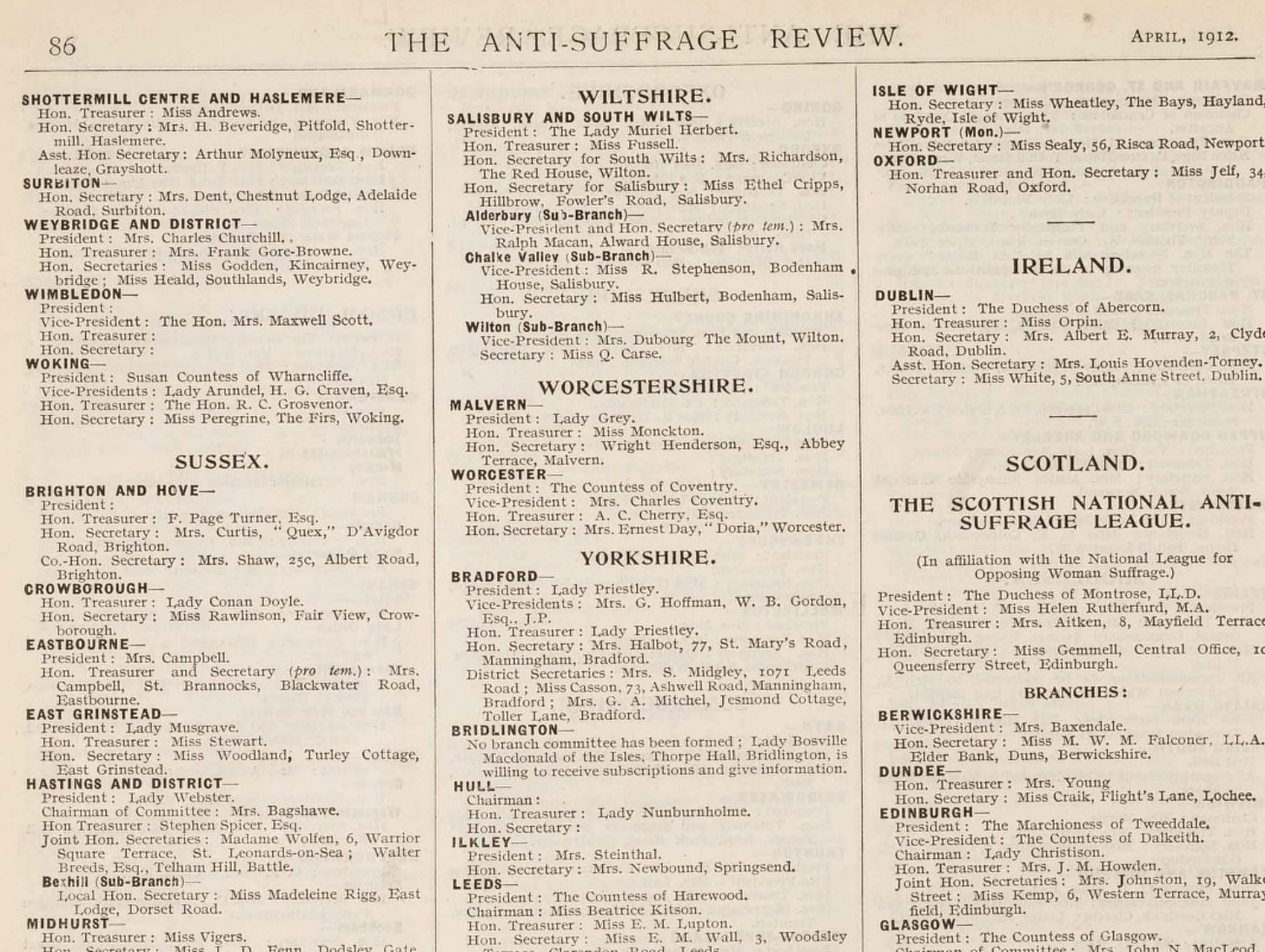

By January 1911, there were branches of the WNASL all across Yorkshire, at Bridlington, Hull, Leeds, Middlesbrough, Scarborough, Sheffield, Whitby and York, with meetings at Scarborough and Manchester reporting “a considerable number of new members and associates”.

The WNASL was also now headed figuratively and politically by the Earl of Cromer and members wore distinctive red badges decorated with a thistle, rose and shamrock. By August, a branch had opened in Ilkley, where its president was listed as being Mrs Steinthal, with Mrs Newbound appointed as the branch secretary.

That same year, a WNASL meeting held in Ilkley was described as a “drawing room” gathering – a smaller, more intimate meeting than those held in the public halls of Manchester.

The issues discussed at these meetings were just the same, including whether or not women would better serve their country by maintaining their influence in the domestic and moral sphere rather than by “meddling” in politics. The irony that by joining the Anti Suffragist League they were doing just that seems to have been lost on many.

These meetings, in Ilkley, were attended by women who often shared similar views to WNASL members like Bertha Hudson, who, in The Anti-Suffrage Review, argued that the suffragists, by blurring the “natural order of things”, were trying to “create an abnormality, a middle sex. If this species had been necessary to the preservation of humankind, God would no doubt have created it”.

The suffragettes were, according to their critics, unchristian. Women, such as WNASL member Helen Page, argued that it was not God’s will that women should interfere in the political affairs of the country, that they had a different role to play and that by trying to exert themselves beyond that, they were flouting God’s will.

Others still felt that the inclusion of women in politics would weaken the empire’s position as the globe's preeminent power and argued that even suffragists such as one Miss Ransom were forced to admit, in a letter exchange with the anti-suffragist Miss Rinder, that comparisons with other countries were futile in the face of Britain's superiority.

While these views today will strike most of us as being alien, narrow-minded and abhorrent, the lines were not always quite so clear cut in the early part of the 20th century. Some who attended the Ilkley meetings, for example, did so because they opposed the suffragettes' use of violence. They weren’t necessarily against a political campaign for increased enfranchisement, more that they didn’t agree with the tactics that some of the suffragettes used or advocated.

Accordingly, these suffragettes were regarded as little more than “violent thugs” who were a threat to social order. Such views often went hand in hand with a feeling, such as those expressed by Yorkshire woman Ellen Theobald, that women should be “better” and not reduce themselves to such base “male” tactics. This view was supported by some of the suffragists themselves, women such as Helen Moyes, the famous Scottish suffragist who never wavered from her position that “you use argument and reason in a cause not militancy, there is no use or value in militancy as a cause”.

In the summer of 1914, members of the Ilkley branch, whose names are sadly not specified, helped at an anti-suffrage meeting in Manchester that was held by Mrs Boutflower, who was particularly concerned with the issue of violence.

The event was considered a success. The members concerned were thanked for their help and it’s clear that the Ilkley branch was becoming involved in events on a wider scale. The news and arguments debated in places such as Manchester were then discussed in the town.

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 meant that the tactics of both sides of the suffragist argument changed. Many agreed to put their differences to one side and unite in the national interest and, as a result, the Women’s Suffrage Review became a slimmer, less frequently published publication while the WNASL meetings in Ilkley became more sporadic before ceasing entirely. By 1915, branch meets were no longer being recorded.

The First World War effectively ended the WNASL and its campaign. As author and lifelong suffragist Ella Hepworth Dixon stated, “this war [has] proved once and for all that women are as useful to the state as men” and that, as a result, they deserved the vote.

In February 1918 the WNASL conceded defeat, writing that “the die is cast and Great Britain alone of the Great Powers has conferred the parliamentary franchise upon women … the country had been committed to this duplication of the electorate on no expressed wish of its own” and whatever their feelings, women in Ilkley, and beyond, now had to accept that decision.